Aster of Pan isn’t your typical post-apocalyptic story. Sure, its world is a harsh one where survival is hard-fought and communities fiercely protect their own with strict rules and a heavy distrust for outsiders. But it’s also full of humanity, hope, and its fair share of humour; where the common thrust of dystopian fiction is to look at how desperation brings out the worst of us, Aster of Pan makes the argument that hope can never truly be extinguished, no matter how bad things get.

In 2068, a handful of makeshift nation-states exist among the ruins of a destroyed civilization that was once France. They all have their own beliefs and rituals, their own ways of life, their own laws and protocols for surviving in a deadly (if beautiful) wasteland. Pan is such a society, one that scrapes by with modest rice production and the scavenging of ruins. It’s an impoverished but mostly happy place—so long as you’re a citizen.

If you’re “un-Pan”, things are a little different. Those not born in Pan can live there and contribute to its survival, but you get no food allowance and limited protection. In Pan, citizens come first. But that doesn’t stop Aster from more or less enjoying her life, after being taken in as a young child who suddenly showed up at the village gates. She dreams of one day being a citizen and gets frustrated with the laws saying she never can be, but for her, Pan is still home.

When the powerful, technologically advanced nation Fortuna sets its imperialist eyes on Pan, all seems doomed. But they’re given a choice: if Pan can best Fortuna in a game known as “Celestial Mechanics”—it’s basically dodgeball, with a ritualistic flair—it’ll be left alone, but lose, and Pan will be just another victim of Fortuna’s expansion. And guess who has an uncanny natural ability when it comes to this game? Aster, that “un-Pan” girl who the future of the nation suddenly depends on.

“Colonialism by way of dodgeball” is certainly a fresh concept, and Aster of Pan really leans into that. It’s a source of plenty of excitement and humour, especially as Fortuna continuously tries to bend the rules—rules of their own creation, it’s worth noting—to give themselves the upper hand, while Aster and the rest of her team keep finding creative ways to keep themselves in a game with ever-moving goalposts. What starts as a pretty standard game of dodgeball winds up becoming something more like paintball, leaving plenty of opportunity for thrilling moments, heroic comebacks, and cheeky quips.

But even with this frivolity, the threat and impact of colonialism is a more sobering them that’s ever present. Fortuna is a power that could easily eradicate any of its neighbours through sheer military might. But it would rather subjugate and assimilate, using cultural and religious prongs to bring other nations under its thumb, with the threat of force always there to encourage compliance. Aster of Pan touches on the consequence of that in the glimpses we get of other colonised nations, their cultures all but wiped out and their resources plundered for Fortuna’s benefit.

But it’s not just the superpower that’s guilty. Pan may have no imperialist ambitions on its neighbours, but its absolute rule against granting citizenship to anyone who isn’t born in Pan to Pan parents shows a different side of the same coin: an insular, nationalist ideology that’s blind to the humanity of all peoples, Pan and un-Pan alike. Aster is an example of how flawed that thinking is, and—fantastical elements notwithstanding—hers is a story echoed the world over.

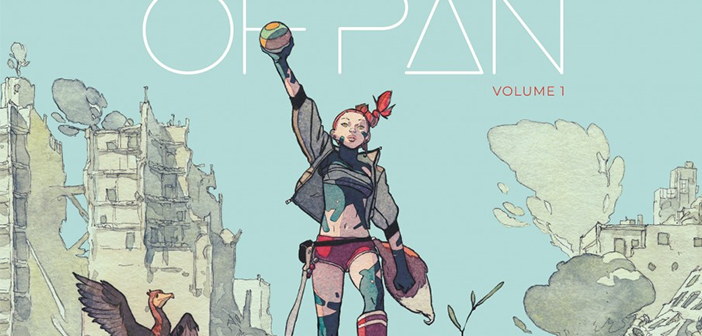

The excitement of Celestial Mechanics and the thoughtful explorations of colonialism play out against a backdrop of watercolour art and a world that’s more interested in the beauty of nature than the desolation of an apocalyptic event. Aster of Pan takes place long after whatever destroyed the world, where the ruins of modern-day France are just old relics that nobody in Pan really understands. Coupled with the colourful artwork, this vision of a post-apocalypse is one of beauty and mystery.

Aster of Pan is a breath of fresh air in the crowded space of dystopian fiction. It’s bright, colourful, and driven by an inalienable belief in hope for a better future—whether that’s through a high-energy, high-stakes game of dodgeball, or by standing up to colonialist ideals.

Aster of Pan is written and illustrated by Merwan, and published by Europe Comics. It’s available now.

A review copy was provided to Shindig by the publisher.